Facts and figures about the livestock industry and the damage it causes are disheartening. However, Gine Zwart from the campaign organisation Feedback EU tells an optimistic story in her guest lecture at the VU. ‘Banks and supermarkets can switch without endangering their core business.’

***

Gine Zwart studied agricultural home economics in Wageningen. In various ways she worked to promote more justice, including at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Kenya and Zimbabwe in agricultural programmes aimed at female farmers. At Oxfam Novib, she coordinated the International Fair Finance Guide. She is now a board member at Feedback EU, an organisation that exposes climate and food injustices.

***

After the US, the Netherlands has been the world’s second-largest agricultural exporter for years, with meat and dairy together forming the largest share of exports. Scientists agree: to combat climate change, we must address large-scale industrial livestock farming.

Global meat production is enormous. Every day, 202 million animals are slaughtered worldwide, of which 1.75 million in the Netherlands. We have vast chicken sheds here. A dairy farmer in the Netherlands usually has at most a few hundred cows. Outside the Netherlands, companies exist that are unimaginably large. The Brazilian JBS is the largest meat producer in the world, with 70 brands in more than 20 countries. It slaughters about 77,000 cows each day.

Mega-companies will never stop or reduce voluntarily

Gine Zwart shares an interesting insight about such mega-companies, including our own FrieslandCampina. ‘They will never voluntarily stop or reduce their activities. If they launch plant-based products, it’s just a small side venture. Their core activity remains meat or dairy production.’ JBS for example, also owns the vegetarian brand Vivera.

Even with technological solutions to reduce emissions – which in practice do not work very well – large livestock companies essentially delay the real solution: phasing out industrial farming. In fact, ‘These companies want only to grow further. JBS announced in 2023 that it aims for a 70 percent increase in global consumption of animal proteins by 2050.’

Look for powerful parties that are (to some extent) willing

The insight that livestock companies will never voluntarily cooperate in reducing livestock farming creates a clear perspective for those who do want to work on such a reduction. Don’t focus your arguments, reports, and campaigns on those companies. Look for parties that may be somewhat willing to cooperate in such a reduction. Parties that are indispensable to the meat industry.

Almost all eyes are on politics. That’s where the rules and conditions are set. Journalist Coen van de Ven concludes in his book Wantrouwen in de wandelgangen that there are 295 accredited journalists and cameramen working around the Dutch Parliament. These are the people constantly jostling to wait for quotes from party leaders and ministers, following all the debates, and networking with everyone in The Hague to immediately report every step forward or backward. Meanwhile, the entire political landscape, from The Hague to the EU and even the United Nations, is under the control of the meat and dairy lobby.

The meat lobby adjusts advice and agreements

In its report Climate Impact of Big Money (in Dutch) Feedback EU mentions that the meat and dairy industries spent 30 million dollars lobbying in the US and 18 million dollars lobbying in the EU between 2014 and 2020. Zwart explains what the meat industry achieves with these investments: ‘At climate summits, the place is teeming with lobbyists. They manage to get agreements adjusted.’ Even at the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change), the UN body the whole world looks to for climate science and climate change solutions.

After pressure from Brazil and Argentina – strongly influenced by domestic meat industry lobbyists – a passage was removed from an IPCC report stating that a ‘shift to diets with a higher proportion of plant-based protein’ in high meat-consuming countries would lead to a significant reduction in emissions. The passage stating that ‘plant-based diets could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by up to 50% compared to the average emission-intensive Western diet’ was also removed.

A study by The Guardian shows that the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) censored, sabotaged, undermined, and victimised staff who tried to highlight the negative impacts of livestock farming. The authors of the only FAO report that openly questioned large-scale livestock farming in 2006 were also obstructed. All of this happened under pressure from meat, dairy, and animal feed producers and countries with high meat production like Brazil, the USA, and Australia.

Find the blockers, movers, and swingers

The conclusion that Zwart and Feedback EU draw from these uncomfortable truths is: look beyond politics. Lobbyists for the good cause don’t have the millions that the meat industry can spend on their own lobbying efforts, so they have to be clever. In targeting their efforts, they use an interesting method. They analyse the power dynamics in a graph. On the X-axis, it shows whether a party or institution is in favour or against reducing large-scale livestock farming. On the Y-axis, it shows whether they have much or little influence. At the top left in the graph are the blockers: parties with a lot of influence who are against change. You can hardly move them. Movers are those who are willing. They are on the right side of the graph. They can serve as an example for the swingers: parties that have not yet made a clear decision.

Zwart: ‘It’s a very nice model, you can do a lot with it. For example, if you’re going to a climate summit, which countries will you spend your energy on? Countries that are swingers, like some countries in Africa. And you use movers as examples: countries like Germany, which are promoting plant-based diets and reducing meat consumption as part of their climate strategy.’

In such a stakeholder model, you can place countries or political parties, but also all the partners involved in large-scale livestock companies. It then becomes clear that banks and supermarkets wield a lot of influence. They are vital to the livestock sector. So, they are high on the Y-axis of ‘influence’, but on the X-axis of ‘in favour or against’, they are almost at zero. They just want to make money. But they can do that without the large-scale meat industry. And they are sensitive to reputational damage. This presents opportunities.

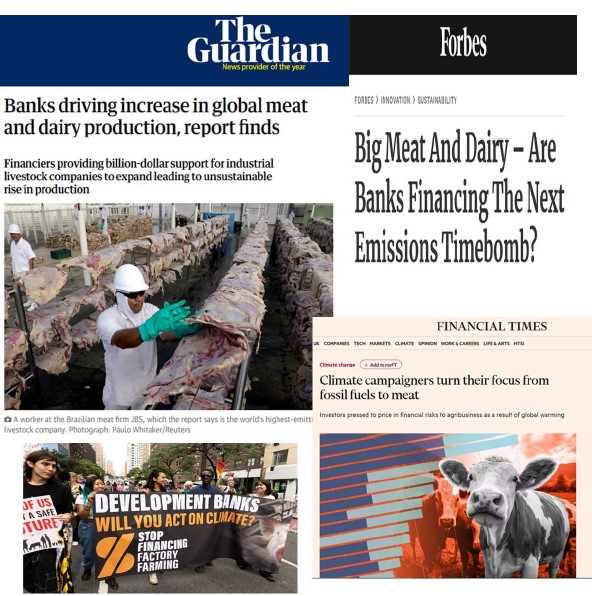

Banks fuel the meat industry

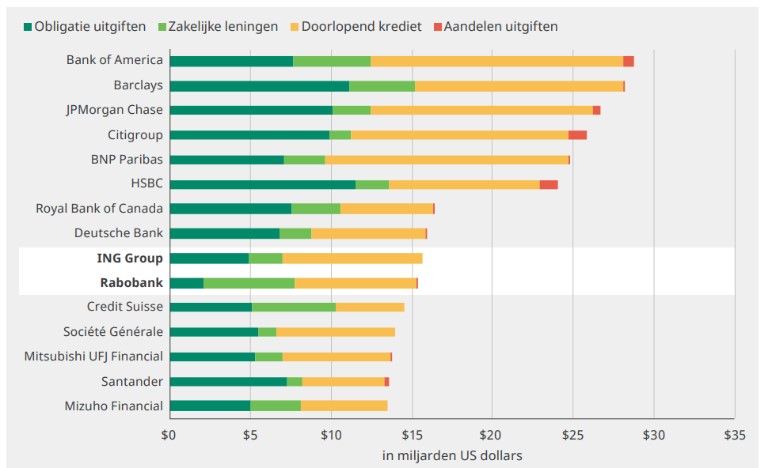

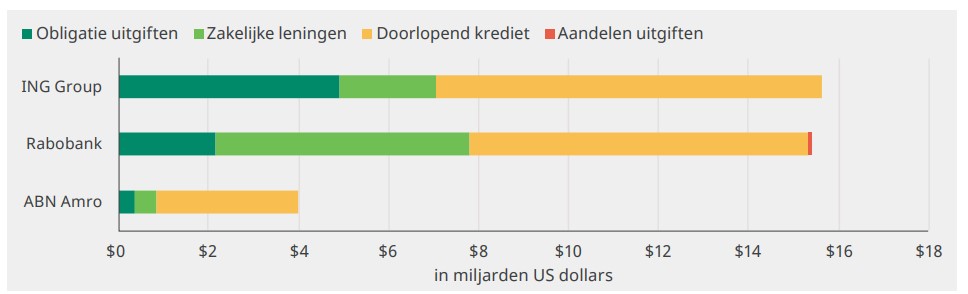

Zwart first illustrates the influence of banks in her lecture. According to Feedback EU, between 2015 and 2022, they invested a whopping 600 billion dollars in the 55 largest industrial livestock companies in the world. Dutch banks ING and Rabobank are among the top 10 banks worldwide that invested most in these 55 companies.

The three largest Dutch banks – ING, Rabobank, and ABN Amro – spent at least 35 billion dollars between 2015 and 2023 financing the 55 largest livestock and animal feed companies in the world. This contradicts Rabobank’s promise to do everything possible to adhere to the Paris Agreement of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Some banks show there is an alternative

Slowly, awareness is growing among the public, industry, and governments that large-scale meat production and consumption are a bad idea for the climate, health, and food security. China even wants to halve its meat consumption. But the banks continue investing, claiming it is up to their clients to work on greater sustainability. Zwart: ‘Rabobank wants to combat climate change by, for example, having bank employees fly less for business trips. Changing their investments is a very different story.’

But there are banks that show there is an alternative. ‘Triodos and ASN Bank do not invest in industrial livestock farming. Among others, Volksbank and Norway’s Norges Bank even pulled money out of the largest livestock company, JBS.’ Does another bank then simply fill the gap? Zwart dismisses this argument. ‘This is a start. It can drive down stock prices in the sector, increase capital costs, and increase the pressure for regulation. Industrial livestock farming is only a small part of the banks’ portfolios, so they can easily sever ties with it.’

Race to the top

She continues: ‘If we encourage the banks that are doing it right, a race to the top could emerge.’ Unfortunately, that’s not happening very quickly. Of the dozens of students in the lecture hall, almost no one knew about the Fair Finance Guide, let alone that they would switch banks. Something that, according to Zwart, is much easier than many people think.

Still, I am excited; I see opportunities. I think again of the hundreds of journalists who stand in the Hague lift jostling for a quote from politicians like Geert Wilders. Some probably think, ‘What am I still doing here, it’s going nowhere.’ Perhaps they could use their microphones and interview talents to storm the boardrooms of our banks. To ask if what was discussed today brings us closer to the Paris goals and greater equality. We live in a capitalist world, big money is in charge. So, if you want to control power, you also have to be there as a journalist.

Supermarkets pretend they have no power

Then there is the other power bloc with much influence in the power field: supermarkets. Zwart: ‘Supermarkets deny that they have much power. They frame it as our own choice, but we don’t ask for crisps or chocolate at the checkout. Five major supermarket chains in the Netherlands decide what we eat.’ They have the power to move farmers and suppliers to provide more sustainable and healthier food. And just like for banks, they only need to shift their attention, their core business remains unaffected. People still need food, and the supermarket remains the easiest place to stock up.

While the race to the top among banks is still slow, supermarkets and producers are doing better, says Zwart. ‘In the Behind the Brands ranking, Unilever and Nestlé were constantly competing for first place.’ Zwart was involved in this ranking, which Oxfam developed based on extensive research. ‘Nestlé would call us when they suddenly dropped from first to second place.’

‘Less meat race’ and letters to ministers

Feedback EU organised the Minder vlees race (Less Meat Race) to showcase what supermarkets are doing to reduce the environmental impact of the meat and dairy products they sell. This kind of campaign targets the public. Behind the scenes, the organisation also does a lot. ‘With the news that Plus supermarkets are only selling organic milk and at the same price as other milk, we approach Albert Heijn to ask when they will do the same.’ Writing letters to politicians and policymakers is also an important activity. The FAO, the UN’s food and agriculture organisation, published a report in 2023 suggesting that more meat production could be a way to generate fewer greenhouse gas emissions. ‘It contained methodological errors. Feedback Global and Feedback EU wrote an open letter to the FAO, signed by about 100 organisations and scientists.’

Important to unravel what is happening

Not that this immediately leads to improvement. ‘But it’s important to unravel what is happening and show that injustices and false claims don’t go unnoticed.’ There’s a lot to do in this area. For example, the Dutch Minister Hermans of Green Growth recently said that we have already picked the low-hanging fruit to green our economy. ‘That’s nonsense; there are still many relatively easy measures we can take to stop further climate change,’ Zwart argues.

Feedback EU also investigated the false claims of supermarkets and wrote a report to confront them with their greenwashing. Zwart knows that Feedback EU’s research reports do not go unnoticed: ‘They are discussed in boardrooms of banks, for example.’ That’s where it needs to happen, she believes. ‘You often hear the phrase: change the world, start with yourself. But that won’t get us very far. We need to tackle the big powers and forces.’

Text: Rianne Lindhout